Interviewer: Siobhán McHugh for National Library of Australia

There can be few Irishmen in Australia with Father Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin’s connections to the struggle for Irish independence between 1919 and 1921. At the time his father, legally trained but working as a sub-editor on the Irish Independent, published a letter from the most wanted man in Ireland, Michael Collins, one of the leaders of the Irish Republican Army waging a guerilla war against British forces in Ireland. Father Mícheál recalls that Collins’ biographer, Piaras Béaslaí, described what happened next:

… four Auxiliary officers rushed into the Independent Office, held up the sub-editor … Mr P O’Sullivan, held revolvers against him, and threatened him with death if he did not reveal where he got it [the Collins letter].

Needless to say this good newspaperman did not give them the information, nor did they carry out their threat. Father Mícheál’s father went on to be one of the first District Justices of the Irish Free State in County Cork.

Growing up in Ireland Mícheál also had a strong connection with Australia. His mother, Sydney born Mary O’Connell, met his father on a trip to visit Irish relatives in the early 1920s.With two of her daughters she was on a visit to Sydney in 1939 when World War II prevented their return home. The next Mícheál saw of them was on his ordination day at All Hallows College, Dublin, in 1952, after which he himself came out and became a priest of the Sydney Catholic Archdiocese. In one sense he had come home and he is sure the presence of his mother helped him to adapt quickly to Australia although he has never forgotten his connection to Ireland and its fight for an independent existence.

Father Mícheál’s commitment to the Irish story is clearly revealed in his work for the Memorial to the 1798 Rebellion in Waverly Cemetery, Sydney. This magnificent structure, he feels, is the most impressive monument of its kind anywhere to a major rebellion in Ireland. In 1953, not long after arriving in Sydney, he was taken to the annual ceremony at the monument on Easter Sunday and from then until 1966 he recited the Rosary in Irish as part of the ceremony. From 1966 it became customary to say a Mass at the ceremony and Mícheál has consistently participated in that event.

Ironically Mícheál’s lasting contribution to the ongoing relevance of the 1798 Memorial is a work of history, ironic because when at school in Ireland long years ago he was considered of little use at the subject. He still recalls the words of his history teacher, ‘Some people make history – O’Sullivan you invent history’. The same teacher would be mightily surprised at Sydney 1798 Memorial – tomb of a man who fought an empire Father Mícheál’s detailed guide to the amazing complexities of the 1798 Memorial – the Celtic designs, the wolfhounds, the embossed shields, the mosaics, the bas-relief heads of the patriots of the 1798 period, and the meaning behind the plaques listing the leaders of 1798, the 1916 Rising and the Maze Prison Hunger Strikers of 1981.

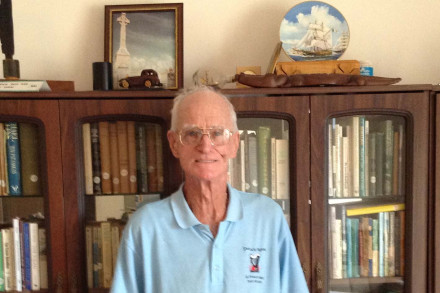

Although retired Father Mícheál still retains an interest in keeping up his skill in the Irish language. Irish music drew him to the céilí dances at the INA although there he feels that at 86 he may soon have to slow down a bit. Despite his long and active life in Australia, and his love of this county, his great joy has always to be back in Ireland visiting with his many cousins.